I have been an Interpretive Planner for museums around the world for over 30 years. When I started in 1992, the term was rarely used. Family and friends still ask: “What is it exactly that you do?” So I thought I would look back over my 30 years in museums, zoos, aquaria and heritage sites to pick out some of the favourite exhibits that I have worked on as a way of explaining the process of interpretive planning and what it is. Here we look at the site research that went into the development of the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts.

When I first walked onto the site of the Central Police Station, Magistracy and Victoria prison in 2008, it was still a decommissioned, one could say abandoned, site. Except of course that in 2007, the Hong Kong Jockey Club had been given the task of running one of the biggest heritage revitalisation projects in Hong Kong, and possibly one of the biggest at the time in Asia. Wandering through forgotten rooms in which people had worked for so many years or in which people’s lives had been so dramatically affected by incarceration or worse, the sense of history was palpable.

It was a privilege to have with me on a number of these occasions former uniformed officers who had worked there – notably Guy Shirra (Old & Bold), Bryan Coak, Charles Ng and Russell Mason. Many of them had memories of arriving as callow youths in the 1960s or 1970s, and tales of times when Hong Kong was a very different place. In particular, the riots of 1967 came up again and again as a period when places like the Central Police Station acted like fortresses and officers would drive to work with one hand on their service revolver (if they had one).

Some of the rooms had a Marie Celeste feeling with full ashtrays left in drawers and unwashed cups seemingly waiting for the next brew. This was especially true when we managed to force entry into a room that used to belong to the Junior Police Officers’ Association. It looked like people had just got up and left for lunch … except that it was nearly a decade ago. Files had been left open, pens in pots, calendars waiting for the month to be turned, coffee rings from coffee cups. It was quite eery.

Superstition and local customs were much in evidence with many shrines to Guan Yu, the traditional deity worshipped by the police and ironically the criminal fraternity alike.

Something else that struck me about the Central Police Station and Magistracy parts of the site was that every time I went on there I usually came across the remnants of a new “mess”, a place to eat and relax but often incorporating a well-appointed bar (making the current re-use of the site for Tai Kwun’s bars and restaurants most appropriate). Suffice it to say that the wheels of the justice system at the time seemed to have been well oiled.

Perhaps the most atmospheric part of the site, however, was the Victoria Prison. With a presence dating back to the very origins of colonial Hong Kong in 1842, walking into prison blocks (the oldest from 1860) filled you with an inexplicable sense of foreboding; except of course it was not so difficult to understand given that people had endured hardships here, including at the hands of the occupying Japanese forces during the Second World War. One of these was Chinese writer and poet Dai Wangshu, arrested by the Japanese military and imprisoned in Victoria Gaol for seven weeks, during which he was badly tortured in the prison. One of his most famous poems called ‘Written in a prison wall’ was about his imprisonment:

If I die here,

My friends, don’t be sad.

I shall live forever

In your hearts.

Dead is only one of you

In a prison under Japanese occupation.

He nursed a deep,deep hatred,

That you must always remember.

When you return and dig up

From the earth his mutilated body,

Please let your vistory cheers

Bear his soul to soar in the sky,

And please place his bleached bones,

On a mountain top to bathe in the sun and the wind:

This, my friends, was the only dream he had

In that dark and dank dungeon.

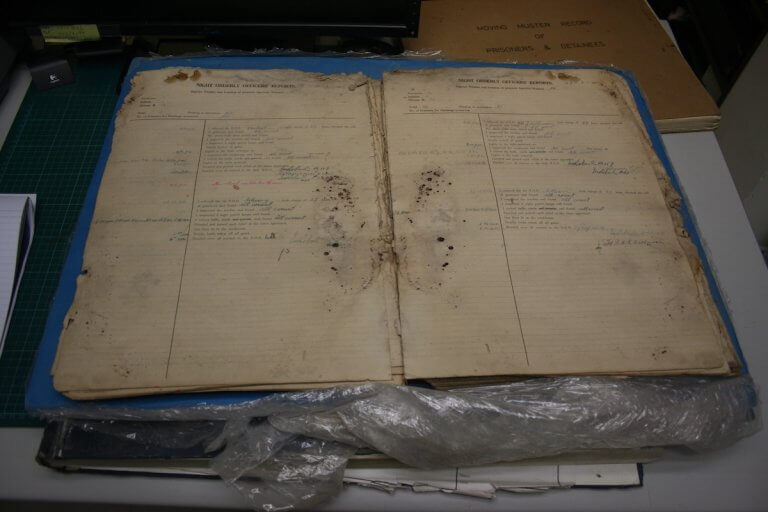

Another great find was the Night Orderly Officers’ Report Book which recorded incidents on a nightly basis, the entries for which end on 8th December 1941 (the day of the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong) and resume on the next page at the end of the war.

However, most poignant of all was our find in what had been a nursery for babies and children of overstay Mainland mothers in the 1980s in D Hall prison block. Some kind soul had tried to brighten the place up a bit by painting a wooden cutout of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse.

Opened to the public as a new heritage resource in 2018, Tai Kwun has received over 13 million visitors. It was recommended by Time Magazine in its “World’s Greatest Places 2018” list and in 2019 granted “Award of Excellence” from the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation.