I have been an Interpretive Planner for museums around the world for over 30 years. When I started in 1992, the term was rarely used. Family and friends still ask: “What is it exactly that you do?” So I thought I would look back over my 30 years in museums, zoos, aquaria and heritage sites to pick out some of the favourite exhibits that I have worked on as a way of explaining the process of interpretive planning and what it is. Here we look at an exhibit in a Tai Kwun prison cell.

The big picture of masterplanning is harder to explain. Working on a site before there is even a building to plan the content, gallery spaces, adjacencies, connections, visitor journey and facilities can all sound a bit abstract. The importance of doing this at an early stage so that the architects can, ideally, design the museum building from the inside out makes more sense when explained. But often the best way to talk about what I do is to bring it down to the level of an individual exhibit.

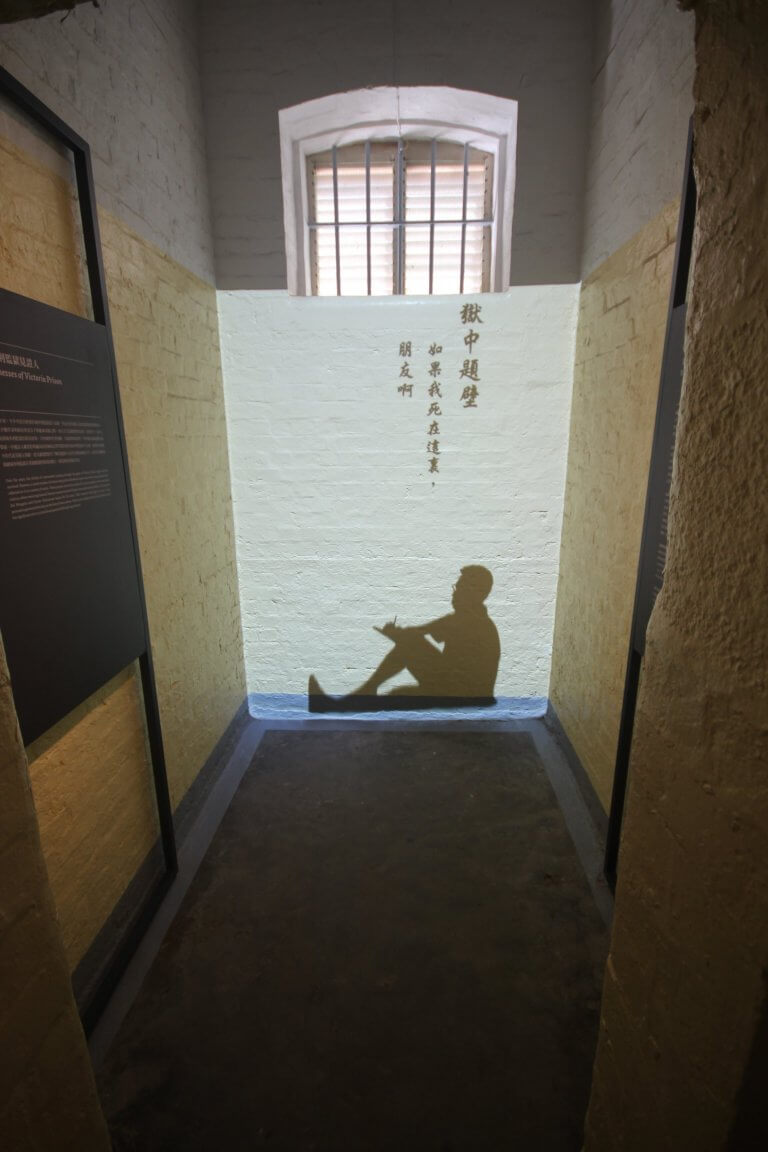

Tai Kwun contains some of the oldest colonial buildings in Hong Kong (formerly the Central Police Station, Central Magistracy and Victoria Prison). B Hall is one of the prison blocks in Victoria Prison. The in-depth research for the Interpretive Plan in 2009 turned up that a number of well-known and fascinating figures had been associated with the Central Police Station and Victoria Prison over its 150-year history. These included Ho Chi Minh, future President of Vietnam, José Rizel, Filipino writer and revolutionary, and in particular Dai Wangshu.

Dai was a Chinese writer and poet, arrested by the Japanese military and imprisoned in Victoria Gaol for seven weeks. He was badly tortured in the prison and released due to health issues. One of his most famous poems was about his imprisonment. He was an important figure in the anti-Japanese movement in Hong Kong, and his experience during the wartime had changed his writing style and made him a famous and respected writer in China.

His poem was called ‘Written in a prison wall’ (translation by Hsu Kai-yu). It was so poignant that I felt that it should be represented within a Tai Kwun prison cell without comment. The interpretive treatment simply projects the poem line by line on the wall of the cell.

If I die here,

My friends, don’t be sad.

I shall live forever

In your hearts.

Dead is only one of you

In a prison under Japanese occupation.

He nursed a deep,deep hatred,

That you must always remember.

When you return and dig up

From the earth his mutilated body,

Please let your vistory cheers

Bear his soul to soar in the sky,

And please place his bleached bones,

On a mountain top to bathe in the sun and the wind:

This, my friends, was the only dream he had

In that dark and dank dungeon.

Exhibit design by Marc & Chantal.