I have been an Interpretive Planner for museums around the world for over 30 years. When I started in 1992, the term was rarely used. Family and friends still ask: “What is it exactly that you do?” So I thought I would look back over my 30 years in museums, zoos, aquaria and heritage sites to pick out some of the favourite exhibits that I have worked on as a way of explaining the process of interpretive planning and what it is. Here we look at the site research that went into the development of The Drug InfoCentre Hong Kong.

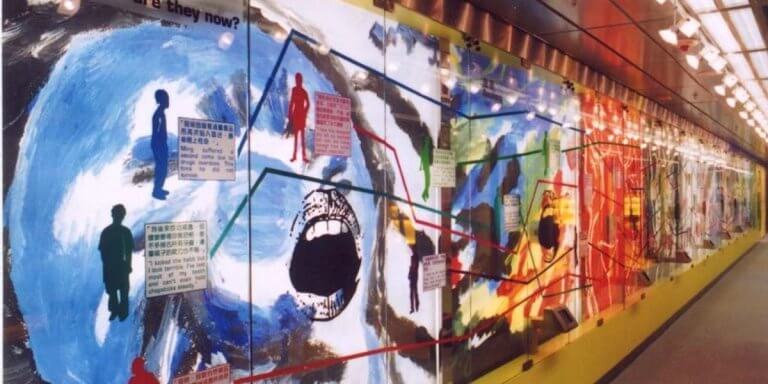

If you look up to the right as you cross the footbridge from the United Centre to Pacific Place in Hong Kong, you might notice a couple of colourful floors perched on top of a podium of a rather grey looking government building. It might surprise you to know that this public exhibition about drugs has been there for over twenty years.

In 2000, the Narcotics Division of Hong Kong came to us with a problem. The Action Committee Against Narcotics had endorsed the development of a “Drug InfoCentre” for Hong Kong funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. As Director of Research for MET Studio at the time, I embarked on an in-depth study of similar public information centres around the world and reports on drugs education produced in the UK, USA, Europe and elsewhere. The overwhelming conclusion was that the notoriously difficult target audience – teenagers – were not interested in hearing from authority figures such as police officers, judges or doctors. They wanted to hear from their peers or people who had “been there and done that”. And that was the approach we took.

The Narcotics Division of Hong Kong were enlightened and visionary enough to endorse this approach and take the risk of not being seen as sufficiently “tough” on the war on drugs. The field research I undertook was fascinating – from visiting the Addiction Treatment Centre on Hei Ling Chau Island to spending a day at a Methadone Clinic in Wanchai. I was even lucky enough to get a personal talk about the current drug trafficking routes and prices from the police’s head of anti-drugs enforcement at the Wanchai Police Station during which a group of officers returned from a drugs raid high on adrenaline.

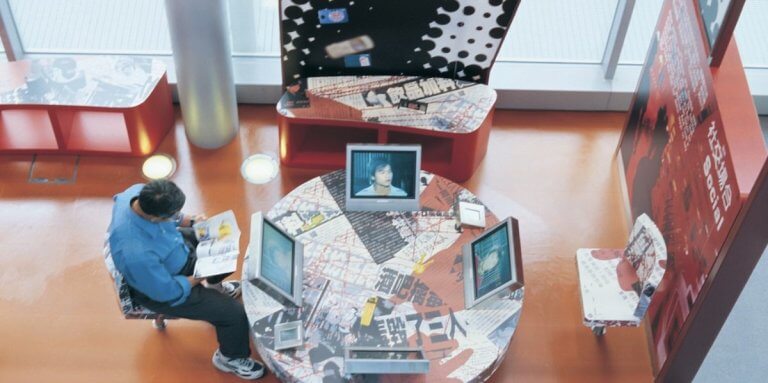

So, we presented the facts about what drugs do to your body on a central spine in the space without any sense of judgement or reference to criminality. Around it, visitors were presented with a more nuanced debate about whether drugs are good or not. They heard testimony from teenagers and parents who had been to hell and back due to addiction.

They could explore case studies (in literal cases) from professionals affected by what they saw in their work with drug addicts but without the wagging finger of so much anti-drug public information.

And they could hear debates between teenagers where it was acknowledged that there was an upside to drugs, even though the downsides outweighed it.

All in all, it was one of the experiences in my museum design career when I really felt the client was listening and that you could make a difference. The Drug InfoCentre opened in 2004 and operated very successfully for 15 years.

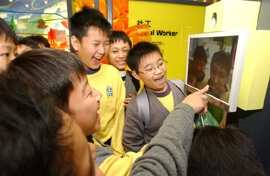

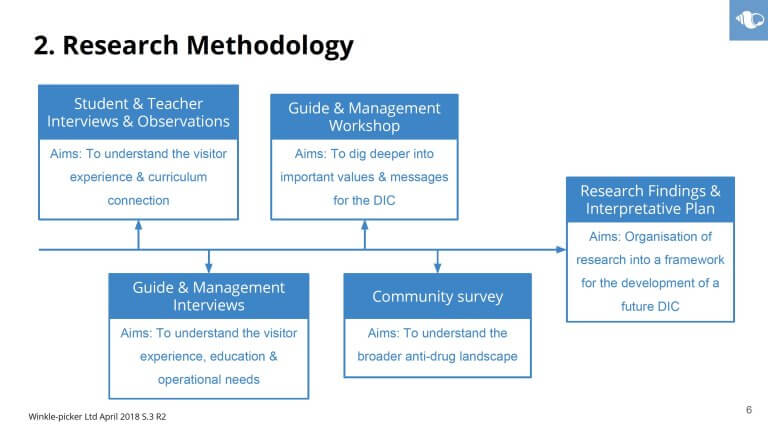

We were then asked back to do a research for an upcoming refurbishment …

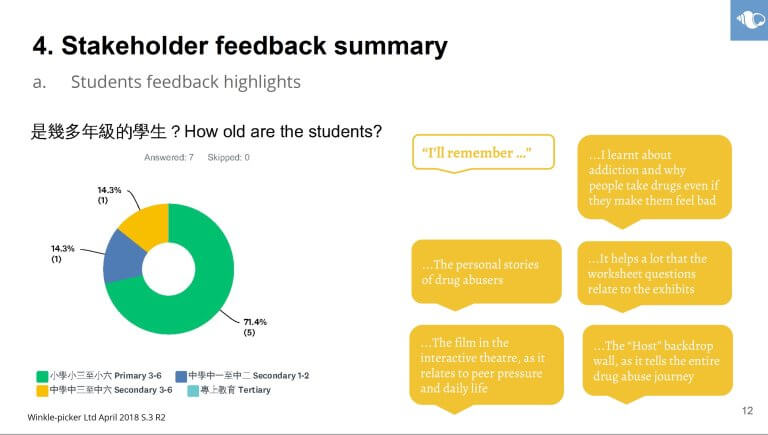

… and workshopping exercise during which we spoke to the operators and educators who used it …

… and consulted extensively with the wider anti-drugs education community and teachers …

… and consulted extensively with the wider anti-drugs education community and teachers …

… to form an Interpretive Plan which was used as the basis for a future refurbishment.