Every day for 30 days we will be featuring a museum object that has inspired or intrigued us, in the hope that “an object a day keeps the doctor away.” We love creating exciting, meaningful storytelling through engaging experiences, but still firmly believe that it is hard to beat the thrill of being in the presence of authentic artefacts. Today’s object is: Turing’s bombe.

The Enigma machine was used by the Germans during the Second World War to encode and decode messages. The machine contained a series of interchangeable rotors, which rotated every time a key was pressed to keep the cipher changing continuously. This was combined with a plug board on the front of the machine where pairs of letters were transposed; these two systems combined offered 103 sextillion possible settings to choose from. The Germans believed Enigma to be unbreakable.

Building on the work of Polish codebreakers, a codebreaking unit was set up in 1939 at Bletchley Park in England under a former WWI codebreaker, Dilly Knox. At first ‘Men and women of a professor type’ were recruited through contacts at Oxford and Cambridge universities. The organisation started with only around 150 staff, but soon grew rapidly eventually involving around 10,000 people.

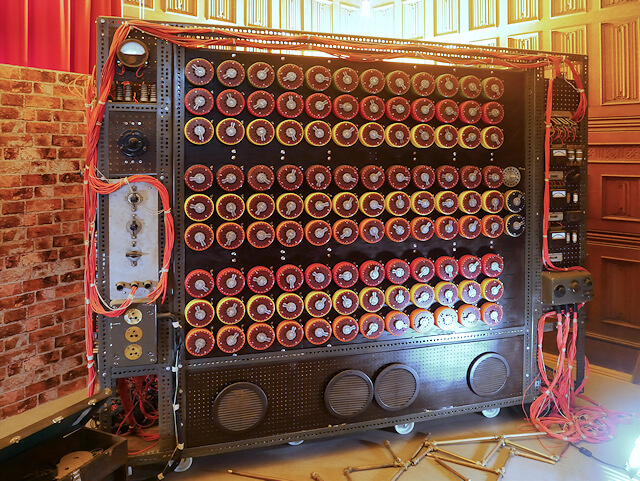

The first bombe was named “Victory”. It was installed in Hut 1 at Bletchley Park on 18 March 1940, based on Alan Turing’s design. The bombe was an electro-mechanical device that replicated the action of several Enigma machines wired together. The bombe was designed to discover the daily settings of the Enigma machines on the various German military networks. Once this was done, all German military secret messages could be read for the rest of the day. This produced vital intelligence in support of Allied military operations on land, at sea and in the air.

Enigma traffic continued to be broken routinely at Bletchley Park for the remainder of the war, contributing significantly to the Allied military operations and so shortening the war. Bletchley Park also heralded the birth of the information age with the industrialisation of the codebreaking processes enabled by machines such as the Turing Bombe, and the world’s first electronic computer, Colossus.

A sad post-script to this story is the disgraceful treatment of Alan Turing after the war. In 1952 he was prosecuted for homosexual acts and submitted to chemical castration treatment as an alternative to prison. Turing died in 1954, 16 days before his 42nd birthday, from cyanide poisoning.

In 2009, following an Internet campaign, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official public apology on behalf of the British government for “the appalling way he was treated”. Queen Elizabeth II granted Turing a posthumous pardon in 2013. The “Alan Turing law” is now an informal term for a 2017 law in the United Kingdom that retroactively pardoned men cautioned or convicted under historical legislation that outlawed homosexual acts

Bletchley Park is currently closed. Check website for details.